Ativistas de direitos humanos temiam que a vitória presidencial [en] do ex-general Otto Perez Molina [en] significaria um retrocesso na justiça de transição da Guatemala. Entretanto, nessa semana, dois eventos marcantes deram claros sinais de que a frágil democracia da Guatemala está amadurecendo.

Em 26 de janeiro, o Congresso guatemalteca ratificou o Estatuto de Roma da Corte Penal Internacional, o qual permite que a Corte Internacional acuse qualquer violador de direitos humanos se a Guatemala falhar em o fazer; no mesmo dia, após anos sendo protegido pela imunidade parlamentar, o ex-presidente Efraín Rios Montt [en] foi questionado pelo seu envolvimento no genocídio de 1.700 indígenas maias em 1982-1983, durante a Guerra Civil de 36 anos na Guatemala [en] (1960-1996).

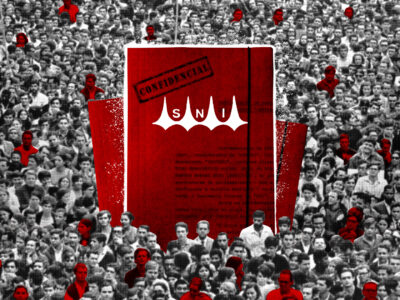

Garoto fica em frente ao nome das vítimas do genocídio. Foto por Renata Avila sob atribuição 2.0 genérica (CC BY 2.0), licença Creative Commons.

No Blog SALTlaw, em um post entitulado “Um bom amanhecer para a Justiça na Guatemala” [en], Raquel Aldana escreve sobre o significado de Rios Montt encarar um processo por genocídio e crimes contra humanidade:

Today was a historic day for Guatemala. A few hours ago, after a long day of heady hearings, a Guatemalan court opened a criminal case for genocide against Retired Military General Efraín Ríos Montt and ordered him detained under house arrest. Now 85, the retired general must face trial accused of being responsible for one hundred massacres, which produced a death toll of one thousand, seven hundred and seventy one victims. Ríos Montt, who until recently enjoyed immunity after serving nearly two decades as Congressman in Guatemala, had been de facto president during the most brutal 17 months of the 36 year-long civil war, between 1982 and 1983.

Ela continua reportando a aparição de Rios Montt na corte:

When asked in court today if he understood the charges he faced, Ríos Montt said into the microphone “I understand perfectly.” Then, instead of making a formal declaration of guilt or not guilt, he stated a preference for silence. Outside the courthouse today, indigenous Guatemalans laid red rose petals spelling impunity no more. Meanwhile, the Guatemalan Congress ratified the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

No blog do Conselho de Negócios Estrangeiros, Natalie Kietroeff expõe [en] a defesa de Rios Montt.

Ríos Montt has made his defense quite clear. Over the past month, he has repeatedly said that he can’t be tried for any human rights violations because he wasn’t in charge of the military’s on-the-ground operations as the country’s political leader. His lawyer has echoed these claims, telling the press recently, “We are sure that there is no responsibility, since he was never on the battlefield.”

Ela segue explicando:

This strategy is a radical new approach in the Guatemalan context. Until now, the military has consistently denied that genocide was ever a part of the civil war. Even the current president, Otto Pérez Molina, said that he doesn’t believe the findings of the UN truth commission, and that he could “prove that [genocide] did not occur,” during the conflict. But Ríos Montt is now arguing not that the atrocities didn’t happen, but that he is not culpable.

While this doesn’t yet amount to an open acknowledgement of genocide, it does suggest that things have changed (if slightly) since the Association for Justice and Reconciliation (AJR) first brought charges against Ríos Montt in 1999. The discovery of mass graves by the Forensic Anthropology Foundation of Guatemala (FAFG) and the tireless work of victims groups in pushing for trials – finally winning convictions for four ex-soldiers this year – has made it untenable for the military to negate the genocide outright, at least in a court of law.

Embora isto ainda não é equivalente a um reconhecimento aberto de genocídio, já sugere que algumas coisas mudaram (mesmo que suavemente) desde que a Associação para Justiça e Reconciliação (AJR) trouxe as primeiras acusações contra Ríos Montt em 1999. A descoberta de grandes valas comuns pela Fundação de Antropologia Forense da Guatemala (FAFG) e o trabalho incansável dos grupos de vítimas em cobrar por processos – finalmente conseguindo condenações de quatro ex-soldados este ano – tem feito ser insustentável para os militares negarem que o genocídio ocorreu, pelo menos na Corte de Justiça.

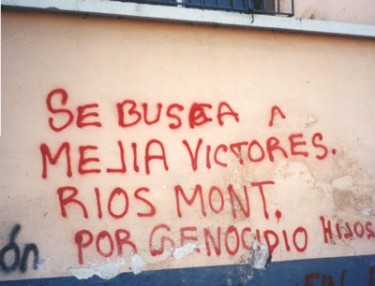

"Procurados. Mejia Victores e Rios Mont por Genocído." Graffiti na Cidade da Guatemala. Foto por The Advocacy Project sob Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-ND 2.0), licença Creative Commons

No Blog Lawyers, Guns and Money [en], Erik Loomis observa o que o processo de Ríos Montt significa para a Guatemala hoje:

Today, Guatemala faces a new period of instability due to the expansion of drug gangs from Mexico and El Salvador into their country and its unfortunately convenient stop on the drug highway to the United States. Whereas thirty years ago, people wanted to dismantle the police force because of its horrifying repression, today people are putting hope in the police as the one thing that could stand in the way of a new generation of shocking violence. Forcing Ríos Montt to face trial for his crimes is not going to solve any of Guatemala’s enormous problems, but it might at least force the defenders of violence in that nation to think twice about their actions.

Mike, no Política da América Central [en], reporta que Ríos Montt teve fiança garantida e permanecerá sob prisão domiciliar durante o julgamento. Mike acrescenta sua opinião:

A tremendous victory for the people of Guatemala and a continuation of what I believe has been a pretty remarkable year-plus of human rights advancement in the region.

Esse dois eventos mostram que, sem fechar os olhos para o passado e para as terríveis atrocidades que foram cometidas durante a Guerral Civil no país, a Guatemala mira em se tornar um país onde os padrões de direitos humanos internacionais são respeitados e encorajados. O fato que o presidente Otto Perez Molina, um ex-general do exército, não interferiu no caso e apoiou a assinatura do Estatuto de Roma dá aos guatemaltecos esperança de que no futuro próximo a justiça chegará mais cedo, antes de os criminosos estarem mortos, muito velhos ou doentes para enfrentar um julgamento.