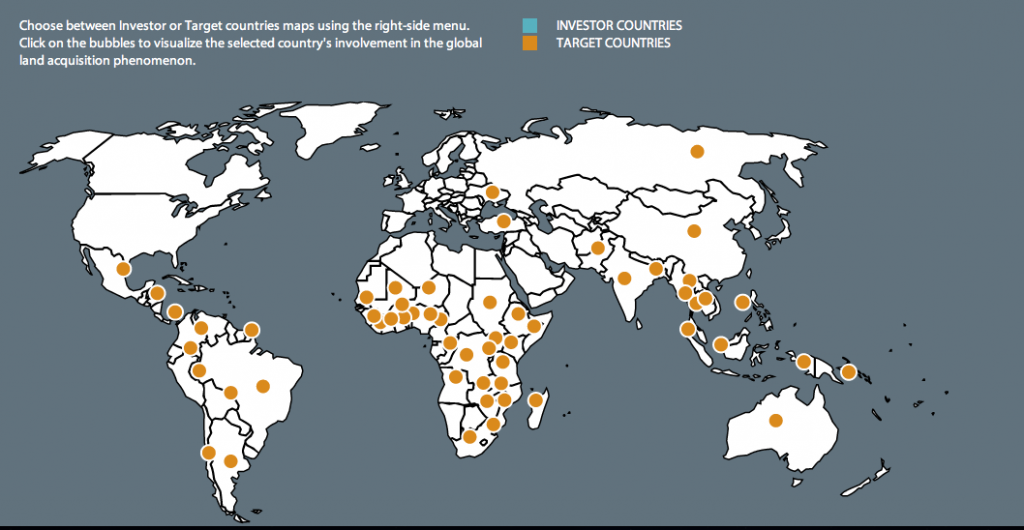

O blog Desenvolvimento Global, do jornal britânico The Guardian, publicou [en] que uma coalizão internacional composta por pesquisadores e ONGs lançou o maior banco de dados [en] do mundo sobre negociações internacionais de venda de terras. É um marco, e põe em perspectiva uma importante questão do desenvolvimento que recebe pouca atenção do noticiário internacional.

O relatório revela que quase 5% das terras aráveis africanas foram compradas ou arrendadas por investidores desde 2000, e enfatiza que isso não é uma novidade, mas afirma que o número desse tipo de negociação aumentou tremendamente nos últimos cinco anos.

Muitos observadores estão cada vez mais preocupados com essas negociações, que normalmente ocorrem nos países mais pobres do mundo e impactam suas populações mais vulneráveis, os pequenos fazendeiros. Os benefícios raramente alcançam a maioria da população, em parte pela falta de transparência nas transações.

Um relatório adicional elaborado pela Global Witness (organização envolvida em questões ambientais e de direitos humanos), intitulado Dealing with Disclosure [en] [Negociando sem Segredos], enfatiza a premente necessidade de transparência nas negociações envolvendo terras.

Alvos são as nações mais pobres do mundo

O relatório da Global Witness informa que foram identificadas 754 negociações de terras, abrangendo 56,2 milhões de hectares e a maioria dos países africanos.

Os países-alvos dessa prática são normalmente os mais pobres do planeta. Aqueles com o maior número de registros de negociações são Moçambique (92 registros), Etiópia (83), Tanzânia (58) e Madagascar (39). Alguns desses negócios chegaram às manchetes dos jornais porque estavam relacionados a manobras para garantir o controle da importação de alimentos nos momentos em que as regiões afetadas encararam graves crises alimentares.A ONG GRAIN já explicou em detalhes a essência de suas preocupações em um extenso relatório [en] publicado em 2008:

Today’s food and financial crises have, in tandem, triggered a new global land grab. On the one hand, “food insecure” governments that rely on imports to feed their people are snatching up vast areas of farmland abroad for their own offshore food production. On the other hand, food corporations and private investors, hungry for profits in the midst of the deepening financial crisis, see investment in foreign farmland as an important new source of revenue. As a result, fertile agricultural land is becoming increasingly privatised and concentrated. If left unchecked, this global land grab could spell the end of small-scale farming, and rural livelihoods, in numerous places around the world.

No Malawi, as negociações envolvendo terras tornaram-se prevalentes em detrimento dos fazendeiros locais. Um relatório de Bangula explica os desafios [en] enfrentados pela fazendeira malauiana Dorothy Dyton e sua família:

Like most smallholder farmers in Malawi, they did not have a title deed for the land Dyton was born on, and in 2009 she and about 2,000 other subsistence farmers from the area were informed by their local chief that the land had been sold and they could no longer cultivate there. […] Since that time, said Dyton, “life has been very hard on us.” With a game reserve on one side of the community and the Shire river and Mozambique border on the other, there is no other available land for them to farm and the family now ekes out a living selling firewood they gather from the nearby forest.

Os fazendeiros em Madagascar compartilham preocupações similares porque não detêm a posse das terras que cultivam e uma reforma agrária efetiva ainda não foi implementada. A associação local Terres Malgaches tem estado à frente das ações de proteção das terras em prol da população local e informa [fr] o seguinte:

Les familles malgaches ne possèdent pas de document foncier pour sécuriser leurs terres contre les accaparements de toutes sortes. En effet, depuis la colonisation, l’obtention de titres fonciers auprès de l’un des 33 services des domaines d’un pays de 589 000 km2 nécessite 24 étapes, 6 ans en moyenne et jusqu’à 500 dollars US. (..) . Face aux convoitises et accaparements dont les terres malgaches font l’objet actuellement, seule la possession d’un titre ou d’un certificat foncier, seuls documents juridiques reconnus, permet d’entreprendre des actions en justice en cas de conflit.

A associação também relata as práticas de uma mineradora chamada Sheritt, em Ambatovy, que criaram rebuliço na blogosfera local por conta das ameaças ambientais [en] à população local e de más práticas comerciais (via MiningWatch Canada [en]):

Sherritt International’s Ambatovy project in eastern Madagascar – costing $5.5 billion to build and scheduled to begin full production this month – will comprise a number of open pit mines (..) it will close in 29 years. There are already many concerns about the mine from the thousands of local people near the facilities. They say that their fields are destroyed ; the water is dirty ; the fish in the river are dead and there have been landslides near their village. During testing of the new plant, there have been at least four separate leaks of sulphur dioxide from the hydro-metallurgical facility which villagers say have killed at least two adults and two babies and sickened at least 50 more people. In January, laid-off construction workers from Ambatovy began a wildcat strike, arguing that the jobs they were promised when construction ended have not materialized. The people in nearby cities like Moramanga say that their daughters are increasingly engaged in prostitution.

Testemunho em vídeo de um trabalhador de Ambatovy.

Soluções para a população local?

A difícil situação dos fazendeiros de Madagascar pode estar em lenta mutação, no entanto. O debate sobre a reforma agrária está andando, de acordo com esta notícia [en]:

According to a paper presented at the 2011 International Conference on Global Land Grabbing, about 50 agribusiness projects were announced between 2005 and 2010, about 30 of which are still active, covering a total land area of about 150,000 ha. Projects include plantations to produce sugar cane, cassava and jatropha-based biofuel.

To prevent the negative impacts of land grabbing, (The NGO) EFA has set up social models for investors, with funding from the UN Development Programme (UNDP). The goal is to help investors negotiate with the people in the area where they want to implement projects, as a way to prevent future problems.

Para prevenir os impactos negativos da tomada de terras, (a ONG) EFA montou modelos [de negócios com critérios] sociais para os investidores, com financiamento pelo Programa das Nações Unidas para o Desenvolvimento (UNDP). O objetivo é ajudar os investidores a negociarem com os moradores das regiões afetadas pelos projetos que desejam implementar, como uma maneira de evitar futuros problemas.

Joachim Von Braun, que trabalhou no Instituto Internacional de Políticas de Alimentos (IFPRI), escreveu [en] o seguinte a respeito dos negócios envolvendo terras:

It is in the long-run interest of investors, host governments, and the local people involved to ensure that these arrangements are properly negotiated, practices are sustainable, and benefits are shared. Because of the transnational nature of such arrangements, no single institutional mechanism will ensure this outcome. Rather, a combination of international law, government policies, and the involvement of civil society, the media, and local communities is needed to minimize the threats and realize the benefits.

A necessidade de transparência na venda de terras também é enfatizada [en] por Megan MacInnes, ativista sênior da Global Witness para as questões de terras:

Far too many people are being kept in the dark about massive land deals that could destroy their homes and livelihoods. That this needs to change is well understood, but how to change it is not. For the first time, this report (Dealing with Disclosure) sets out in detail what tools governments, companies and citizens can harness to remove the shroud of secrecy that surrounds land acquisition. It takes lessons from efforts to improve transparency in other sectors and looks at what is likely to work for land. Companies should have to prove they are doing no harm, rather than communities with little information or power having to prove that a land deal is negatively affecting them.